What are the plant hardiness zones?

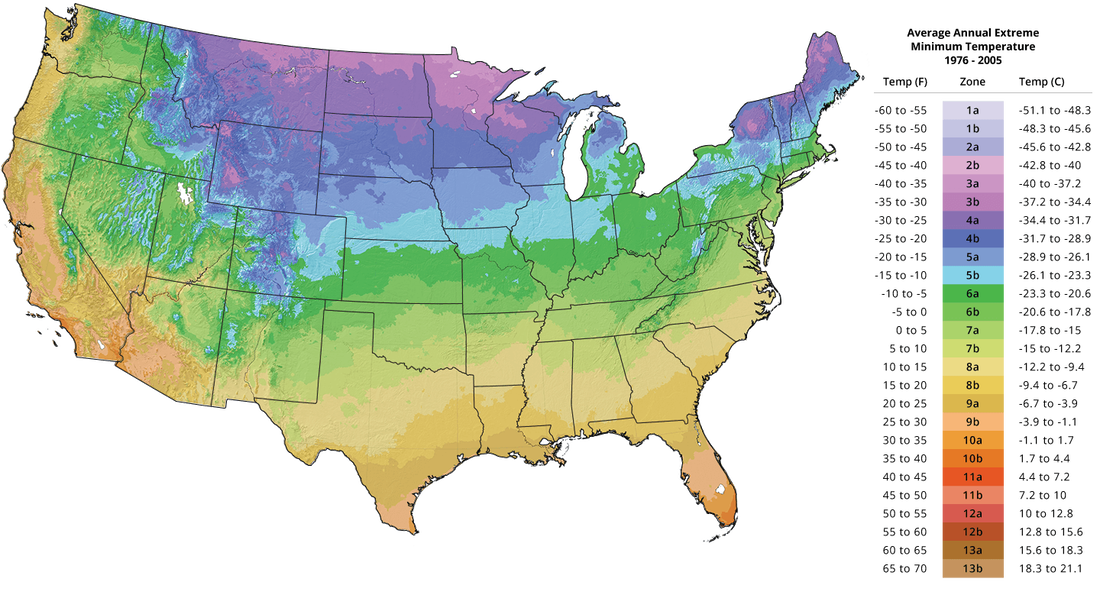

The USDA Hardiness Zone Map divides North America into separate planting zones; each growing zone is 5°F warmer (or colder) in an average winter than the adjacent zone. If you see a hardiness zone in a gardening catalog or plant description, chances are it refers to this USDA map.

What zone am I in?

To find your exact USDA Hardiness Zone, enter your zip code here

You'll notice the latest map breaks down the zones even further into an A and B, but most seed packets and catalogs will just reference the number and are not that precise.

You'll notice the latest map breaks down the zones even further into an A and B, but most seed packets and catalogs will just reference the number and are not that precise.

Who makes this thing anyway?

The latest version of the USDA Zone Map was jointly developed by USDA's Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and Oregon State University's (OSU) PRISM Climate Group, and released in January of 2012. To help develop the new map, USDA and OSU requested that horticultural and climatic experts review the zones in their geographic area, and trial versions of the new map were revised based on their expert input.

Compared to the 1990 version, zone boundaries in the 2012 edition of the map have shifted in many areas. The new map is generally one 5°F half-zone warmer than the previous map throughout much of the United States. This is mostly a result of using temperature data from a longer and more recent time period; the new map uses data measured at weather stations during the 30-year period 1976-2005. In contrast, the 1990 map was based on temperature data from only a 13-year period of 1974-1986.

However, some of the changes in the zones are a result of new, more sophisticated methods for mapping zones between weather stations. These include algorithms that considered for the first time such factors as changes in elevation, nearness to large bodies of water, and position on the terrain, such as valley bottoms and ridge tops. Also, the new map used temperature data from many more stations than did the 1990 map. These advances greatly improved the accuracy and detail of the map, especially in mountainous regions of the western United States. In some cases, they resulted in changes to cooler, rather than warmer, zones.

Compared to the 1990 version, zone boundaries in the 2012 edition of the map have shifted in many areas. The new map is generally one 5°F half-zone warmer than the previous map throughout much of the United States. This is mostly a result of using temperature data from a longer and more recent time period; the new map uses data measured at weather stations during the 30-year period 1976-2005. In contrast, the 1990 map was based on temperature data from only a 13-year period of 1974-1986.

However, some of the changes in the zones are a result of new, more sophisticated methods for mapping zones between weather stations. These include algorithms that considered for the first time such factors as changes in elevation, nearness to large bodies of water, and position on the terrain, such as valley bottoms and ridge tops. Also, the new map used temperature data from many more stations than did the 1990 map. These advances greatly improved the accuracy and detail of the map, especially in mountainous regions of the western United States. In some cases, they resulted in changes to cooler, rather than warmer, zones.

How accurate is it?

Great for the East

The USDA map does a fine job of delineating the garden climates of the eastern half of North America. That area is comparatively flat, so mapping is mostly a matter of drawing lines approximately parallel to the Gulf Coast every 120 miles or so as you move north. The lines tilt northeast as they approach the Eastern Seaboard. They also demarcate the special climates formed by the Great Lakes and by the Appalachian mountain ranges.

Zone Map Drawbacks

But this map has shortcomings. In the eastern half of the country, the USDA map doesn't account for the beneficial effect of a snow cover over perennial plants, the regularity or absence of freeze-thaw cycles, or soil drainage during cold periods. And in the rest of the country (west of the 100th meridian, which runs roughly through the middle of North and South Dakota and down through Texas west of Laredo), the USDA map fails.

Problems in the West

Many factors beside winter lows, such as elevation and precipitation, determine western growing climates in the West. Weather comes in from the Pacific Ocean and gradually becomes less marine (humid) and more continental (drier) as it moves over and around mountain range after mountain range. While cities in similar zones in the East can have similar climates and grow similar plants, in the West it varies greatly. For example, the weather and plants in low elevation, coastal Seattle are much different than in high elevation, inland Tucson, Arizona, even though they're in the same zone USDA zone 8.

The USDA map does a fine job of delineating the garden climates of the eastern half of North America. That area is comparatively flat, so mapping is mostly a matter of drawing lines approximately parallel to the Gulf Coast every 120 miles or so as you move north. The lines tilt northeast as they approach the Eastern Seaboard. They also demarcate the special climates formed by the Great Lakes and by the Appalachian mountain ranges.

Zone Map Drawbacks

But this map has shortcomings. In the eastern half of the country, the USDA map doesn't account for the beneficial effect of a snow cover over perennial plants, the regularity or absence of freeze-thaw cycles, or soil drainage during cold periods. And in the rest of the country (west of the 100th meridian, which runs roughly through the middle of North and South Dakota and down through Texas west of Laredo), the USDA map fails.

Problems in the West

Many factors beside winter lows, such as elevation and precipitation, determine western growing climates in the West. Weather comes in from the Pacific Ocean and gradually becomes less marine (humid) and more continental (drier) as it moves over and around mountain range after mountain range. While cities in similar zones in the East can have similar climates and grow similar plants, in the West it varies greatly. For example, the weather and plants in low elevation, coastal Seattle are much different than in high elevation, inland Tucson, Arizona, even though they're in the same zone USDA zone 8.